Eimear Morrissey - Producer

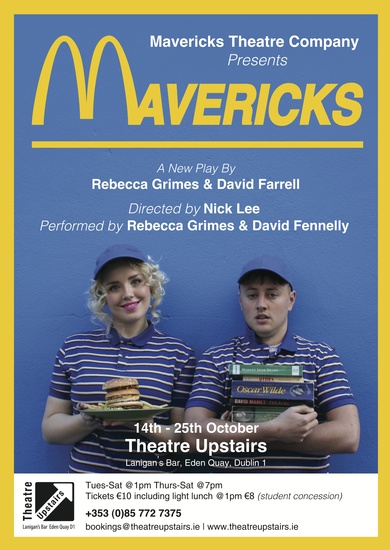

Mavericks | Rebecca Grimes and David Farrell

"Grimes, who plays Chewy, and David Fennelly who plays Ben, are just so damned attractive, and have such good stage presence and discipline that you sit there and suffer with them through all the impossible dreams... Grimes and Fennelly are sharply directed by Nick Lee in a design by Kate Moylan, lit by Zia Holly. It's charming lunchtime fare at Theatre Upstairs."

- Emer O'Kelly, The Sunday Independent

"It has the endearingly self-satirising concept of two young people putting on a show about two young people putting on a show, but these two tackle it with such enthusiasm, such adept skill and such tongue-in-cheek humour that it becomes impossible to be anything but charmed by their performances. Rebecca Grimes and David Fennelly work with great precision at a frenetic pace and with excellent comic timing."

- Michael Moffatt, The Irish Mail on Sunday

"We've had plays about actors before, but Mavericks enthusiastically pushes it one step further... a play about actors making a play about making a play. Mavericks depicts their struggles through a series of speedy vignettes... Fellow actor Nick Lee directs, and while the genesis of the play could have resulted in in-jokes and navel-gazing, the piece is made for a general audience."

- Eithne Shorthall, The Sunday Times

Before Colour | by Peter Dunne

REVIEW Published 21/09/2008 | 00:00 Sunday Independent

THE Fringe is not supposed to be about dreary old text-based work; it's supposed, in the Dublin Fringe's own phrase, to "push the envelope.

So why does it always seem that some of its best and most thought-provoking work seems to fall into the category of text? Could it be that old-fashioned thought and discipline are the best way to performance excellence? Just a thought.

Hollywood noir and the Hollywood Gothic tale have inspired more than one writer in the past, sometimes with alarmingly bad results. But Peter Dunne's Before Colour for Wicked Angels (at Bewley's Cafe Theatre) is anything but bad; in fact, it has genuinely camp humour and some very chilling moments. It concerns a movie mogul and his studio star wife during the Great Depression, the days of the silent movies.

It nods in the direction of Christina Crawford's horribly credible memoir of her monstrous mother Joan; it also nods in passing to Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?.

All right, Before Colour does go a bit all over the place in its psychological motivation, and it is the mogul's daughter who seems to have least to complain of (she's the one of three sisters who isn't prostituted by her father for the studio investors or pushed into murder to avoid scandal) who ends up mutilating herself by cutting off her fingers. But if you have a fondness for the outsize and outrageous in your classic movie entertainment, it's great gas.

%20.jpg)

Pool (no water) | by Mark Ravinhill

REVIEW Published 14/10/2008 | Evening Echo - Cork

A sharp case of art stealing from life

This is a nice and nasty satire on the way art pillages life for material is given a tight and effective production here in the New Directors Festival.

To get a sense of who playwright, Mark Ravenhill, might be targeting in this play, think Damien Hirst or Tracey Emin as the play is about the creation of a piece of conceptual art from an unexpected source.

Creation is probably the least suitable word for the making of art in the circumstances as this is deep into the territory of art as theft.

A group of artists find that a friend is left unconscious after diving into a pool at night – with, you guessed it, no water. They visit her lying misshapen in her hospital bed; “We’ve spent our whole lives hunting it out, we know there is beauty in it.”

And so they start photographing her for an art installation. Director Mark Rogers and an intelligent cast of Charlie Murphy, Dave Farrell and Eimear Morrissey, catch the plays queasy moves between gauche confessional and tripped out, debauched artist manifesto. From the space between, the playwrights agenda squeezes through.

Given Ravinhill’s taste for the sensational, what comes through in this play is a surprisingly tightly argued satirical riff.

One of the characters is left with the rueful reflection, “I’m so glad art is gone away and now we can be people.” Throughout this spiky drama there is a clear-eyed picture of art stealing from life and offering little back except the possibility for advancement in a willful and debased art world.

Rebecca McCormacks minimal design, thoughtfully lit by Eamon Fox, make this a worthwhile production of a sharp little satire, even though some might find the language a bit too salty.